In architecture, there are years that produce new forms—and years that restore discipline. The period around 2026 belongs to the latter. Not because a spectacular aesthetic idea has suddenly become something everyone copies, but because the standard by which we judge spaces is shifting. This change doesn’t arrive as a manifesto. It shows up in decisions: in what remains, what disappears—and what is allowed to return to the interior without having to justify itself.

Over the past decade, the market has been obsessed with control. Control of colour. Control of sheen. Control of texture. Control of irregularity. Control of the “handcrafted look”. The industry has taken simulation so far that it can now imitate what once seemed almost impossible to replicate: accidental variation, patina, traces of time. At a certain point, interiors began to look as if they all came from the same material library, the same palette, the same rendering set. The problem isn’t minimalism as a language—the problem begins when minimalism turns into routine instead of a decision.

And that is precisely why, in spaces that have become too smooth, there is now a growing need for something that may sound old-fashioned, but is actually radical: that material is allowed to be truthful again, that surfaces become readable again, that interiors regain a sense of architectural stability. Not as “ethics” in the marketing sense, but as a form of elementary honesty: material should no longer be a backdrop—it should be substance.

Within this shift, handmade traditional terracotta tiles do not appear as nostalgic decoration, but as something far more concrete: a floor that carries the space—in the literal sense. Not because it is “warm” as an adjective, but because it has a thermal and tactile reality. Not because it wants to be “rustic”, but because it is not uniform by nature—and it is precisely this non-uniformity that gives a space measure, calm, and depth.

If 2026 has a “trend” at all, it’s the return of standards.

Material truth is not poetry—it is a standard of specification

The term “material truth” often sounds like philosophy. Like something you write elegantly into a project presentation and then forget. In practice, however, it is the opposite: material truth is a standard of specification. It is the point in the design process where the visual idea ends—and the reality of execution begins.

Material truth means that a material is not chosen because it “looks like” something else, but because it is what it is. Not as a concept, but as a constructive and tactile parameter. A truthful surface is one you can read: where it comes from, how it is made, how it reacts to light—and how it behaves in use. Those are four questions an architect asks before even speaking about “style.”

That is the difference between a material chosen for atmosphere, and a material chosen for architecture.

Atmosphere can be bought; architecture must be built.

In recent years, the industry has offered atmosphere on a mass scale—because atmosphere sells quickly. It is easy to photograph, easy to render, easy to repeat. Architecture, however, has an uncomfortable quality: it must work when the camera is off. It has to survive the day, the year—and many years after. Material truth is precisely that discipline: choosing materials that can withstand changes in light, wear, moisture, and temperature differences, and remain not “untouched,” but dignified.

And here lies the core: in 2026, more and more projects are trying to escape what could be called “perfect inertia.” Interiors no longer want to feel lifelessly stable. They want to be stable in a different way: to change without falling apart. To gain traces of use—without those traces being read as defects.

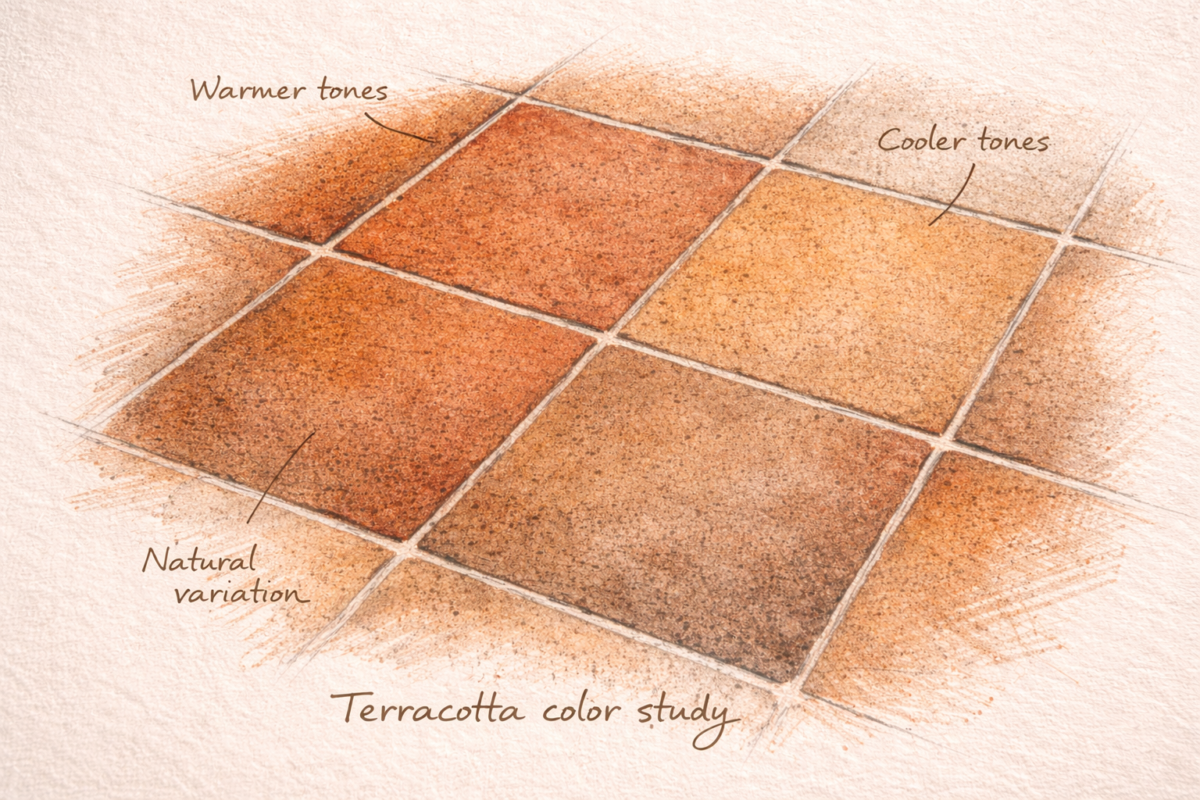

Handmade traditional terracotta tiles hold an advantage here that industry can hardly reproduce convincingly without slipping into imitation: they are alive from the very beginning. Not because they are “irregular,” but because they carry layers within them—in colour, tonal depth, and micro-texture. They are not a surface without information, but a surface that holds its own process inside it.

2026 as the end of a certain kind of perfectionism

We shouldn’t pretend that perfectionism has disappeared. It’s still here—it has simply changed its shape. Instead of demanding perfectly smooth surfaces, it now demands surfaces that look perfectly “natural.” This is the market’s new trap: even naturalness can become a template.

What is truly changing, however, is our relationship to imperfection. In the past, deviation was treated as an enemy—something that had to be hidden. Today, in serious projects, deviation is understood as information. Not in the sense that poor workmanship is celebrated, but in the sense that variation is accepted as part of an architectural decision—not as the result of a compromise.

For this reason, 2026 can be read as the end of one kind of perfectionism: a perfectionism that equates quality with uniformity. Quality is not uniformity. Uniformity is an industrial goal. Quality is a material’s ability to retain meaning even when it cannot be fully controlled.

In interiors—especially on the floor—this becomes impossible to ignore. The floor is the hardest test. Walls can remain untouched for years; floors cannot. A floor is constant use, constant contact, constant change. If the floor material lacks truth, it quickly becomes a problem: scratches look ugly, stains read as damage, shine looks cheap. If the material has truth, the trace does not become a defect—it becomes patina.

This is not a romantic narrative, but a technical reality: a material that can take on traces without losing aesthetic integrity is architecturally stable.

Handmade traditional terracotta tiles can be exactly that—when they are chosen correctly, installed professionally, and treated properly. They are not a “carefree” material—and they don’t need to be. They are a material that demands respect. In return, they give something back that many industrially smooth surfaces cannot offer: a natural relationship with time.

Surface is an architectural decision—not a final decoration

One of the most important shifts in the language of contemporary design is the return to an understanding that surface is part of how a space is constructed—not merely a decorative finish.

In many projects of the last years, materials became a “skin”: an interchangeable layer that changes with the chosen image language. Floor as texture. Wall as texture. Everything as texture. But an architect knows this is not quite true. The floor is orientation. The floor is measure. The floor is acoustics. The floor is temperature. The floor is movement. The floor is rhythm.

Terracotta—especially in handmade, traditional form—restores seriousness to the surface. You cannot treat it like a film. It has thickness, mass, porosity, a response to light. Once it is laid, it does not disappear into the room. It becomes its foundation.

What is interesting is that terracotta is returning precisely in spaces that are not “Mediterranean” in the classical sense. It appears in strict, minimalist—sometimes radically reduced—projects, because there every material must have a reason. Terracotta has one.

In spaces with fewer elements, material becomes louder. If the material is false, the lie is loud. If the material is true, truth becomes calm.

Tactility is not a “feeling”—it is a design parameter

In practice, tactility is often underestimated because it is difficult to quantify. But that does not mean it isn’t real. Tactility often shapes how a space is experienced more than the purely visual impression—yet it is spoken about far less.

Handmade traditional terracotta tiles remain tactile even when finely finished, because the microstructure of the surface is not industrially “ironed out.” That microstructure has consequences: how light catches the surface, how shadow spreads, how calm a room feels—even when it is almost empty.

This is where the difference lies between reflection and presence. Many industrial materials produce reflection: they look “clean” because they mirror light. But reflection is visually restless. Presence is different: the material doesn’t reflect—it absorbs light, holds it, and returns it softly.

Terracotta, in this sense, is a material that “carries” light. And that is exactly why it never becomes boring in well-lit rooms: it doesn’t stay the same throughout the day. It shifts in tone, depth, and temperature. This is not decoration. This is behaviour.

For architects, this is decisive: terracotta can stabilise spaces that are highly reduced. It brings depth without adding “design.” There is no need to compensate with textiles or objects. The depth is in the floor.

“Warm Minimalism” as a result—not a goal

Warm minimalism has become popular as a term because it describes what happens when modern spaces grow tired of coldness. For architects, however, the term itself matters less than the mechanism behind it.

The mechanism is clear: minimalist spaces depend on material. When material is reduced to industrial uniformity, a space becomes cold and generic. When a material returns that has weight, minimalism becomes warm—without becoming decorative.

This is the key point: warmth is not an addition, but a consequence.

Handmade traditional terracotta tiles are one of the most direct ways to ground minimalism. They do so without breaking discipline. They do not demand that a space become rustic. They do not demand a change of language. They simply bring back what has been missing for a long time: material that does not apologise for being real.

Variation as controlled complexity

One of the greatest fears with handmade materials is variation. Clients often see it as a risk: “What if it becomes too colourful? What if it doesn’t look like the photo? What if it doesn’t fit?” The architect stands between the desire for liveliness and the responsibility for the outcome.

With handmade traditional terracotta tiles, however, variation is not chaos—it is controlled complexity. It is not accidental in the sense of being “without order.” It is the result of a process that is stable, but not industrially uniform.

This is exactly what makes possible what matters most today: designing spaces that are not generic, yet remain precise.

With terracotta, variation is not perceived as a pattern, but as depth. In good projects, this depth carries the seriousness of the space: the floor is not a backdrop, but a foundation.

And here lies an important distinction: decorative variation draws attention. Architectural variation holds a space together.

Patina as a project horizon

The most mature projects share one thing: they are planned to look good not only on the day of handover, but after five years—and the best ones after ten look even better.

That is the horizon of patina. Many contemporary materials do not have patina. They have degradation.

Patina means that the material changes—and gains value through that change. Degradation means that it changes—and loses value through that change.

Terracotta has patina because it is mineral, porous, and layered. With correct treatment and care, wear does not read as a defect, but as life.

For architects, this is essential: the client does not receive an interior that must constantly be “protected,” but a space that is allowed to live. And a space that is allowed to live will be loved. And a loved space is cared for better than a space that is merely preserved.

In 2026, more and more people—especially in high-end private projects—are looking for exactly this: materials that are not “luxurious” because they are expensive, but because they possess dignity.

Terracotta as an architectural point of balance

When you enter a space with a terracotta floor, you don’t just receive colour and texture. You receive balance. You sense something that prevents the room from becoming too cold, too sterile, or too “digital.”

In recent years, interiors have increasingly been created from the screen. Renderings became more real than construction sites. Materials that look perfect in a rendering are not always good in real life. Render loves uniformity. Life does not.

Render has become more real than the construction site. Materials that look good in a rendering are not automatically good in real life. Render loves uniformity. Life does not.

Terracotta is not “render-friendly” because it is difficult to control when all you want is an image. It is not a flat texture. It is a material that requires real contact.

And perhaps this is the most important reason for its comeback: not because it is new, but because it stands as the opposite of digital aesthetics. It brings space back to the body.

Originality without the pressure of originality

The paradox of contemporary design is simple: everyone wants originality, but everyone uses the same tools. That makes originality in form increasingly difficult. When everyone has access to the same references, platforms, and moodboards, “new” quickly becomes just another variation of the familiar.

Originality therefore shifts into material.

You don’t need to invent a new geometry to create a space that stays in memory. It is enough to choose a material that is real—a material with character.

Handmade traditional terracotta tiles deliver exactly this kind of originality without spectacle. They don’t create a “wow” moment in the first five seconds. They create a “stays with you” moment after an hour. This is serious architecture: it doesn’t shout. It endures.

Terracotta is not a final layer: it is a system

In a serious specification, terracotta is not treated as a “surface.” It is understood as a system: substrate, adhesive, joint, protection, maintenance. That is the standard. What changes in 2026 is the growing willingness of many clients to accept a system—when it is clear why.

That is why communication today is different: what is being sold is not the “look,” but the logic of the material.

The architect must know: terracotta is not a material chosen because of a photograph. It is chosen because of what it will do within a space. How it receives light. How it behaves in contact with water. How it is cleaned. How it ages.

When this logic is communicated clearly, terracotta becomes one of the rare materials that can be both traditional and contemporary, rustic and precise, warm and disciplined.

That is rare.

And that is why it is returning.

Conclusion – 2026 brings architecture back to its foundations

If we had to summarise this moment, it would not be a “new age of aesthetics.” It would be a new age of standards.

Spaces do not need to look innovative in order to be relevant. They need to be real. They need to be material. They need to be tactile. They need to be allowed to change—without losing their meaning.

In this sense, the return to material truth and craftsmanship is not a trend that will pass. It is a course correction—a return of architecture to itself.

Handmade traditional terracotta tiles are not decoration within this correction, but an argument. Not because they are “beautiful,” but because they are serious. Because they carry light. Because they withstand time. Because they remind a space that it is not an image, but life.

And that is why 2026 will be a year in which we ask less, “What is modern?”—and more, “What remains?”

Because materials that remain share one common quality: they don’t need to explain themselves. It is enough that they are there.